“What is this film about? It is about a Man. No, not that particular man whose voice we hear from behind the screen... It’s a film about you, your father, your grandfather, about someone who will live after you and who is still you. About a Man who lives on the earth, is a part of the earth and the earth is a part of him, about the fact that a man is answerable for his life both to the past and to the future.” – Andrei Tarkovsky

Still from the film Sans Soleil by Chris Marker (1983)

A spiral in the mind’s eye takes over the expanse of the cinema screen. A woman in full technicolor gifts white flower after white flower to people attending an animal’s funeral. A bus driver’s pristine white gloves enact a balance with the road at the slight twitch of his wrists, this way and that. People stand by the seaside waiting, waiting, waiting somewhere on the coastline of the African continent.

I took N to see Sans Soleil, a French documentary film from 1983, directed by Chris Marker, whose title translates to sunless or without light. Although I would hesitate to go as far as say without life, given that the film was replete with images of it; from the innocence of children playing on a hill to the dancing bodies of a crowd, to the carcasses of cows and men garnered equal on a plane of dust. I’ve often seen symbols of death as symbols of life too. I interpret the end as having a ‘before’, a starting point from which they propel, similar but distinct like concentric circles or the plot points of a spiral.

The film’s main preoccupation is centered on themes I have found myself gravitating towards for the better part of three years. Sans Soleil looks at time, and by extension memory, as the great and universal equalizer of all living things. He explores this philosophy through archival footage and the remnants of our visual language (our collective memory). I’m cultivating a religious devotion to all iterations and imprints of time, to understand what tethers me to this universe, what tethers anybody.

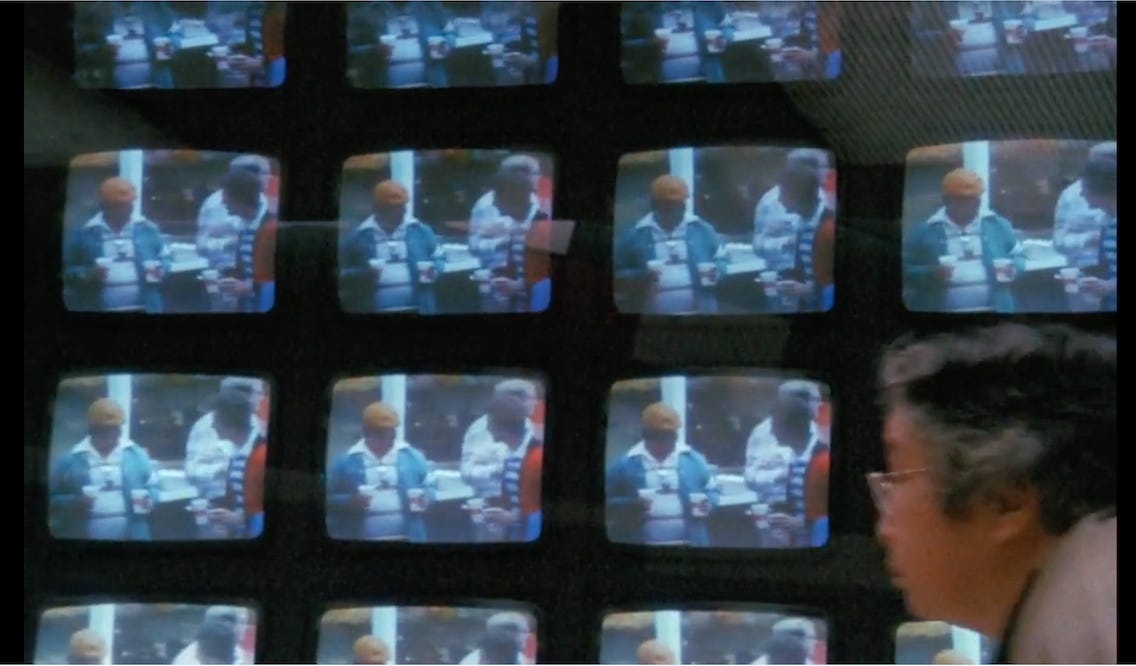

Still from the film Sans Soleil by Chris Marker (1983)

I have always sought out truth. As a child my mother urged me to find it within scriptures; in the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and in the Doctrine and Covenants — which is to say the terms and conditions of our miserable existence as the minutiae of ‘god’. All I found, in the best of times, were beautiful improbabilities. The poetry of those willing to aggrandize themselves to be replicants of god’s image, indebted, a cog in his great and wonderous machine. At worst, I found the fragmented ripples of greed, of manipulation and the segregation of a society that was pitied against each other for an infinite crusade against, what each side considered to be, the newest iteration of ‘evil’.

I quickly learned that parents were people too, and as people they were subject to the same impulses that drove others. The urge to find solace in a community, to find some(thing)one to blame for the injustices of life, and the urge to believe in something greater than themselves in an act of self-sacrifice. An attempt to forge purpose out of the chaos. For a time, I played along, understanding their need, seeing it written on their faces.

Still from the film Sans Soleil by Chris Marker (1983)

In the film the narrator, voiced by Florence Delay, takes the viewer through images of Japanese attendees visiting monuments to Christianity in the form of a bust of the pope and other gilded emblems of god. Placed on plinths inside of a shopping centre those walls are shared by sculptural figurines of gigantic dildos and a series of homages to the Japanese erotic art, called Shunga, in the carefully positioned and oozing bodies of taxidermized monkeys. Meaning, I’ve found, is made in the minds and cultures of those who receive it.

Through Japan and its culture, Sans Soleil asks the viewer how are we different from other animals or even, non-living things. By juxtaposing scenes from the yearly funeral proceedings for pandas that have passed on, with scenes of the ritualistic burning of dolls in a communal pit, and the colloquial ceremony of paying your respects by pouring a large bottle of sake on a loved one’s grave, we feel the metamorphosis of meaning reverberate. All points lead to one. We are, after all, subject to the same guiding hand. Not of god but of time. This erodes us all.

Through reflections on Alfred Hitchcock’s psychological thriller Vertigo -- a film whose own central plot utilizes metaphors to explore a sense of disorientation, and the loss of control involved with questioning an established reality – and a collage of clips showing the eyes of passerby, Sans Soleil presents the elegant spiral that exists within us. This spiral, enacted from our relationship with time, builds the foundation of our relationship with meaning. By resurfacing time’s effects through the eyes of the people both completely aware of (as in the clips of those in Guinea), and in some cases as oblivious to (the footage of passerby in Japan) the watchful socket of the camera, meaning within memory is exhibited for all to see.

Still from the film Sans Soleil by Chris Marker (1983) featuring a quote by T.S. Eliot

My dad got on just fine with his English. We were sat at the registration desk at a school, filling out forms, finalizing my entrance paperwork to join 5th grade mid-year. It was November, I knew this because the snow had not broken through the sky but the clouds still visibly winced at the impending pressure. His accent was thick and at times his grammar was incorrect, often replacing a he for a she or a she for a he — showing in his nonchalance the flexibility present in these terms — but despite these discrepancies he made himself understood. The woman at the registration desk spoke to him slow, directly in his face was if he were a child who was unable to understand what was being said, from her body language alone or the cues present by the context of the situation.

My dad smiled and allowed her to believe what she wished. He is a man of respect that does not lack intellect and, luckily for this woman and all iterations of her form, he has always had great patience. After a while the woman directed her conversation towards me, a child, expecting me to translate despite my father’s clear understanding. The request for translation was made to compensate for her own lack of understanding, rather than his. This he knew, despite the sting it left. Later on that week, at church, he expressed his frustrations with the perception imposed on him by gringos with his friends on their walk from sacrament to priesthood’s first lesson.

I learnt religion’s purpose in the solace he found that day. In order to create mutual understanding we need to pin-point a shared space to start from. A place from which to stake claim, to connect, to formulate questions, a place that allows us to orient ourselves with the hopes of retracing our steps within the great expanse of time, within our own memories. Only then, tethered against some form of reality, can we begin to move forwards into the unknown. While my father’s tether has always been his religion, mine are the markers of time — my own memory and the artificial collective memory of visual media. Each marker serves as a mirror from which to reflect our personhood and as a way to understand, not just ourselves, but those around us despite the differences we uncover along the way.

Still from the film Sans Soleil by Chris Marker (1983)

In the clips of people going about their lives and in the visual reminders of the indiscriminate hand of death, Sans Soleil forms meaning for the viewer only after making contact with the body. In the eyes, through the eyes, we see meaning take form. This is a documentary, not of parts, despite being composed of fragments but rather to highlight a whole. We can only speculate what is hidden beneath the surface of the eyes of strangers we see on the screen, to close that gap, we lean within ourselves to understand the ‘out’. We call to our own minds, to our own subconsciousness in order to formulate universal understanding. This is what Chris Marker executes with precision and perhaps to some degree, a healthy dose of intuition.

As Andrei Tarkovsky so poignantly mentions in his book Sculpting in Time when discussing the importance of artists in recording and reflecting human history through the exploration of life, “the artist … is capable of going beyond the limitations of coherent logic, and conveying the deep complexity and truth of the impalpable connections and hidden phenomena of life.” (pg 21) The truth of Sans Soleil is rooted in our way of viewing and understanding the world.

Through Marker’s own eye (his camera) and in the eyes of those nameless cameramen who comprise the archival material used in the film, we grasp at meaning that is both familiar and peculiar to us in an attempt to connect. The poetry of this film lies equally in the mundane, in the quiet rituals of cultures unlike our own (in the West), in the aftermath of war, in the joy of playing an arcade game that simulates real life and the fleeting if not ephemeral qualities of our own bodies. If we were to view ourselves through the lens of time, as Chris Marker shows us we can do, then we would know with certainty that we are all one in the same. Flesh and blood, driven in the same direction and bound by the exact same rules applicable to all matter in the universe.