AD Seeks Answers, Pt 1: Donald Draper & Peggy Olson

Mad Men, Minority Report, Nara Smith, Coco Chanel ... questions unfolding before our transparent eyes

I’ve been rewatching Mad Men with N. He hadn’t seen it before and since David Lynch’s recent passing, I couldn’t find the words to explain to him why Lynch became so obsessed with it. Watching it felt like the only way to tether.

For those who haven’t seen it (really you must), it’s a show set in the height of NYC’s advertising boom. Centered around the characters of an ever-evolving ad agency with the aloof and irresistible creative director, Don Draper, at its helm. The show follows the characters, most notably; Don Draper (Jon Hamm), Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss) and Joan Harris Holloway (Christina Hendricks) among others, through March 1960 to November 1970 by cataloging the changes in advertising trends. Through the rise and fall of brand partnerships, the evolution of design and the relationships between the male and female characters, we see an imprint of American history embed itself into the show.

When watching Mad Men, you get a sense for the dissatisfaction of Don and Peggy. Both characters, whose approach to copywriting is similar to an artist’s approach to their work, become frustrated with client intervention; especially when they request to change an idea from something with artistic merit into something overly commercial, shallow or overdone. They find themselves woeful at the limitations placed over their creativity and resent trading a magnumopus for coupon codes.

An example of this is when Peggy suggests a bean-ballet commercial for Heinz Baked Beans, shot with micro-photography where the bean’s slippery bodies can be seen pirouetting straight into a can. The Heinz team quickly veto this idea with confusion on their brows and while they ultimately settle for a poetic rendition of ‘dinner with mom’, their disapproval is clear; don’t mistake this for art, we’ve got products to sell.

Stan and Peggy delivering the ‘bean-ballet’ presentation to Heinz (Mad Men), courtesy of AMC

For Don and Peggy, their work means more to them than as a representative tool for the production of capital. By propelling a product’s image into the minds of the masses, they are also changing the way the American public view themselves. Don and Peggy’s success and ultimately their downfall lies in their ability to be absorbed by the lives of their consumers and of the changing culture that surrounds them. They are both a form of ‘transparent eyes.’

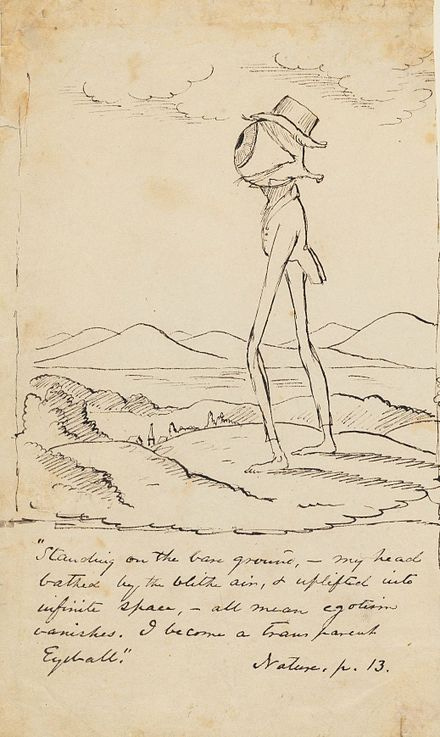

The transparent eyeball is a philosophical metaphor coined by American transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson and is often described as a lifestyle where the eye, ie person, is absorbent of their natural surroundings, rather than reflective of them. This means someone will take in everything that surrounds them, traditionally referring only to natural elements, and they will seek to understand it deeply. Later they will share this knowledge with others through alternative means. They act alongside the natural world, rather than allowing it to bounce off them as they remain unchanged.

This ability allows someone to be a witness to nature rather than a contradictory force. The idea was later adopted by the American photographer Walker Evans, who expanded its definition to include the man-made, to encompass the rapid urbanization that occurred after Emerson and the social changes that took place as a result of the Great Depression, which Evan’s experienced within his own lifetime. Evan’s then utilized the metaphor to refer to a type of photographic skill where the artists align their vision “with Emerson's original desire to absorb and be absorbed into nature, to become a transparent rather than simply reflective eye." In this case, Don and Peggy, are both of their time and because of it.

When at a loss for an idea they visit the movies. When going through something difficult, they choose to create from it.

"Transparent eyeball" as illustrated by Christopher Pearse Cranch. 1836-1838

The tensions between the characters’ ability to create in line with their surroundings, and their need to create as a means to an end (profit), is heavily explored throughout the show. Don’s second wife, Megan, challenges his view of the ad industry through her connection to her artistic friends and Marxist father, and Peggy’s boyfriend pens her a letter denouncing the work she’s done for a problematic company in an attempt to save her. Their different approaches to writing in relation to and with the world eventually leads to their separation. Don and Peggy are both at odds with their responsibilities and in love with the act of creating it. Their battle isn’t with a tricky client, laws limiting the way certain products are advertised or even with bad products, but rather with a system that imposes productivity over artistic value.

As a result of capitalism, the characters in the show turn to self-destructive behaviours; drinking, screwing strangers behind their partners backs, workaholism, self-mutilation and, when the future seems too difficult to bare for some, even death. While watching the show we are reminded of how deep the claws of capitalism really go and how affected we are by its total control over the work of artists or artistically-minded people.

Growing up in America I remember so many ads that became formative to how I viewed myself. The 1991 “L’esprit de Chanel” ad where Vanessa Paradis is nothing more than a bird in a cage, made me yearn for my own weightlessness as a kid while making it clear of my future limitations as a woman. Or the Versace SS 2000 ad I first saw in a Vogue issue at the library with Amber Valleta in a wide open tangerine top leaning back against a mustard suede pillow. Turquoise snake skin belt, purple silk trousers, bleach blond hair; the fantasy of womanhood and the false promise of an appearance that would never come to a non-white child like me. Now, as an adult with a fully developed frontal lobe, I recognize the faults behind building a nostalgic connection with the images of persuasion.

‘Coco L'esprit de Chanel, Vanessa Paradis 1991’ by Jean Paul Goude

I think about the extremes that capitalism has imposed. These days, every person is the embodiment of a walking ad. Nara Smith, the ultimate influencer, is selling the crafted image of herself and her perfect family in order to be eligible to sell other products that generate her capital. What is the fantasy she is trying to produce? One of a wholesome traditional woman. What do we lose in the process? The idea that we could be, no, should be, anything else.

Ads have hooked themselves onto our every word too. The scene from the 2002 film The Minority Report, where a computer biometrically scans Tom Cruise’s borrowed retinas in order to show him personalized ads in the form of holograms, is not too dissimilar from now. I think about a trip to Japan or I whisper it to my husband in the privacy of our home and the next day ‘Jacks Flights’ is being promoted to me on my Instagram. I sense a spot growing on my chin and the cream to combat it appears on my lap. We are so closely attached to everything there ever was that there is no more need for the artistry behind an ad.

Personalized advertising as shown in The Minority Report, 2002

And so I think back to Donald Draper, the metaphorical man behind the ads trying desperately to find something to sooth the ache within him. Or Peggy Olson, the metaphorical woman who aims to expand the way women in society are viewed and I know their “realities” can no longer be our own. Both of them peer into our collective human consciousness, finding plot-points to play a game of connect the dots, forming something beautiful out of a daunting and mechanical task. Through this they feed themselves, they build comfortable lives and yet it is also through this that they suffer.

Social reality is affected by the changes in cultural price points, which were traditionally explored in the artistry of ads but have since been replaced by the ad of the self. The idea of viewing the world as a transparent eye to process it through our art has been inherently tied with capital since the advertising boom era that Mad Men so carefully reconstructs. As the advertising shifts from print, to commercials, to influencers, to personalized pop-ups and beyond, we move further and further away from the promise that artists will be able to create without having to abandon the comforts brought on by a steady salary.

I get the distinct sense that with every new change brought on by AI — a tool used primarily as a way to further embed capitalism into the lives of everyone — that we will be forced to separate our art making from our jobs. What I haven’t quite figured out is how then will we be paid for our transparent eyes? What will we exchange for our ability to respond to the world around us?

(to be continued …)

AD seeks answers is a small series devised around the cross-roads between ADs, capitalist realism and art. In true Through the Eye of a Needle fashion, it is deeply personal, inquisitive and tangential. Subscribe for more!